“On Tuesday morning, October 16, 1962, shortly after 9:00, President Kennedy called and asked me to come to the White House. He said only that we were facing great trouble…That was the beginning of the Cuban missile crisis-a confrontation between the two giant atomic nations, the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., which brought the world to the abyss of nuclear destruction and the end of mankind.” The Attorney General of the United States, Robert F. Kennedy, wrote these words in the beginning of his book Thirteen Days, A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Not only was he the Attorney General, Robert was the President’s brother and his most trusted advisor.

Robert was extremely protective of his brother, especially since becoming President. He was very protective, almost to the point of being brutal to other cabinet members whom did not agree with the President. After all, Robert believed it was the President’s cabinet, his advisors, and the military that let his brother down during the Bay of Pigs. It was not going to happen again.

I cannot imagine how the members at the first meeting, October 16, 1962, must have felt. They were called to the White House, specifically the Oval Office, for reasons unknown. This was never a good sign. When they arrived, the news was that of potential nuclear showdown between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. Just before this October surprise, the Russians had contacted Robert to discuss an atmospheric test ban treaty. Now, here they were placing nuclear warheads 90 miles from the American coastline. Robert summed it up in Thirteen Days, “The dominant feeling at the meeting was stunned surprise. No one had expected or anticipated that the Russians would deploy surface-to-surface ballistic missiles in Cuba.”

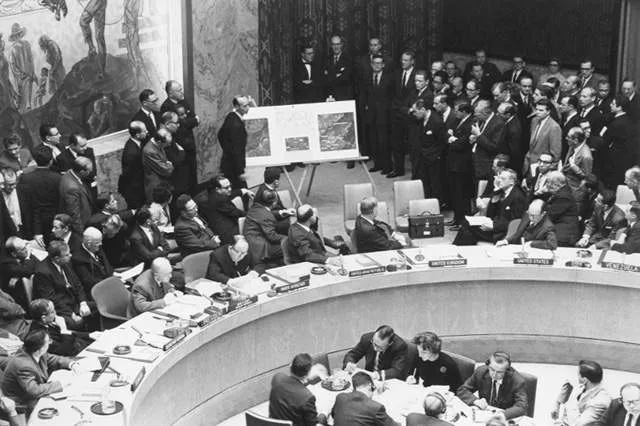

A U-2 spy photo reveals a medium-range ballistic missile base with labels detailing various parts of the base. Circa October 16, 1962

As a result of arial photography, the missiles were discoverd south of Havana. Fourteen canvas-covered missile trailers were identified along with their missile bases. At first, the President resorted to a simple binary position of whether or not the missiles were active, yes or no? In the book, Listening In, The Secret White House Recordings of John F. Kennedy, President Kennedy ask the following questions of his cabinet in reference to activation of the nuclear missiles. “How long have we got? We can’t tell, can we, how long before it can be fired?”

In response to his questions Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, replied. “This is important, as it relates to whether these, today, are ready to fire, Mr. President. It seems almost impossible to me that they would be ready to fire with nuclear warheads on the site without a fence around it…But at least at this moment there is some reason to believe the warheads aren’t present and hence they are not ready to fire.” With this reassurance from McNamara, President Kennedy felt confident he had time to respond to Russian’s recklessness. Any knee-jerk reaction could start a nuclear war, he wanted time to think.

On October 18, 1962, the general consensus of those close to the President believed a first military strike would only hurt other alliances with the U.S., specifically West Germany. Kennedy concluded that a strike against Cuba would ultimately lead to a Soviet reprisal against West Berlin. On October 18, 1962, Kennedy dictated a private statement, for historical reference, which clearly lays out his thought process using the views and beliefs of his advisors. From Listening In, Kennedy noted, “During the course of the day the opinions had obviously switched from the advantage of a first strike on the missile sites and on Cuban aviation, to a blockade…When I saw Robert Lovett…He felt that the missile…the first strike would be very destructive to our alliances. The Soviets would inevitably bring about a reprisal.” President Kennedy was thinking about the larger picture. A picture that not only included the U.S., Cuba, and the Soviet Union, but; Berlin, West Germany, and other countries in the world.

However, as soon as consensus are built, they fall apart. Robert Kennedy, in Thirteen Days, described how the President may have placed the seed of doubt within his own cabinet. “By Thursday night, there was a majority opinion in our group for a blockade…However, as people talked, as the President raised probing questions, minds and opinions began to change again, and not only on small points. For some, it was from one extreme to another-supporting an air attack at the beginning of the meeting and, by the time we left the White House, supporting no action at all…The President, not at all satisfied, sent us back to our deliberations.” What was agreed to was that the President would address the nation on Sunday, October 21, 1962, regarding the crisis and he did not want to do this without a decisive plan in place.

Finally, on Saturday, October 20, 1962, Robert’s frustration was noted. They could not come up with a consensus. His brother, the President, was in Chicago visiting Mayor Richard Daley. Originally, the President wanted to send either Robert, or Kenny O’Donnell (President Kennedy’s most trusted assistant) to Chicago. It is rumored that neither of them wanted to face Mayor Daley’s wrath. However, because Daley contributed significantly to Kennedy’s narrow, 8,000 vote victory in Illinois in 1960, whenever he called, the President had to go. Once he was there, Robert called the President to request he return to Washington D.C. immediately because a consensus on what to do could not be reached.

Because Kennedy did not want the public or the press to suspect anything before he addressed the nation, he had to come up with an excuse to leave Chicago without awaking suspicions. So, he suddenly came down with a cold, accompanied by a fever. The press and Mayor Daley was told that the President was sick and needed to return to Washington D.C. Robert wrote in Thirteen Days, “We met all day Friday and Friday night. Then again early Saturday morning we were back at the State Department. I talked to the President several times on Friday. He was hoping to be able to meet with us early enough to decide on a course of action and then broadcast it to the nation on Sunday night. Saturday morning at 10:00 I called the President at the Blackstone Hotel in Chicago and told him that we were ready to meet with him. It was now up to one single man. No committee was going to make this decision. He canceled his trip and returned to Washington.”

Although the President seemed to have made up his mind concerning the use of a blockade, the military continued questioning the President’s reasoning. They pursued a path of military options, such as: the Air Force takes out the missile bases, followed by an invasion of American ground troops, or, a simultaneous ground invasion, along with Air Force bombardment of the missile bases (the most dangerous of all options on the table). Unless the plan called for a military invasion of Cuba, the military was against it.

The trump card the military attempted to play against President Kennedy-he was weak on defense. Furthermore, the use of a blockade was shown as a weak response to the current situation. After all, according to the Air Force, the President had blundered the Pay of Bigs operation. This attitude toward the President by the military is seen in the exchange between the President and Air Force Chief of Staff, General Curtis LeMay. From Listening In:

- LeMay – “I think that a blockade, and political talk, would be considered by a lot of our friends and neutrals as being a pretty weak response to this. And I’m sure a lot of our own citizens would feel that way, too. In other words, you’re in a pretty bad fix, Mr. President.”

- JFK – “What did you say?”

- LeMay – “You’re in a pretty bad fix.”

- JFK – “You’re in there with me.”

President Kennedy with Air Force Chief of Staff, General Curtis LeMay (middle), circa 1960’s.

This exchange also reveals how the President considered his decision a decision everyone had a say in. Whether it was right or wrong, they all had some sort of wager in the outcome. If the world was going to be on the brink of nuclear war, President Kennedy wanted to hear from everyone possible in order to make a decision. He was looking for a consensus.

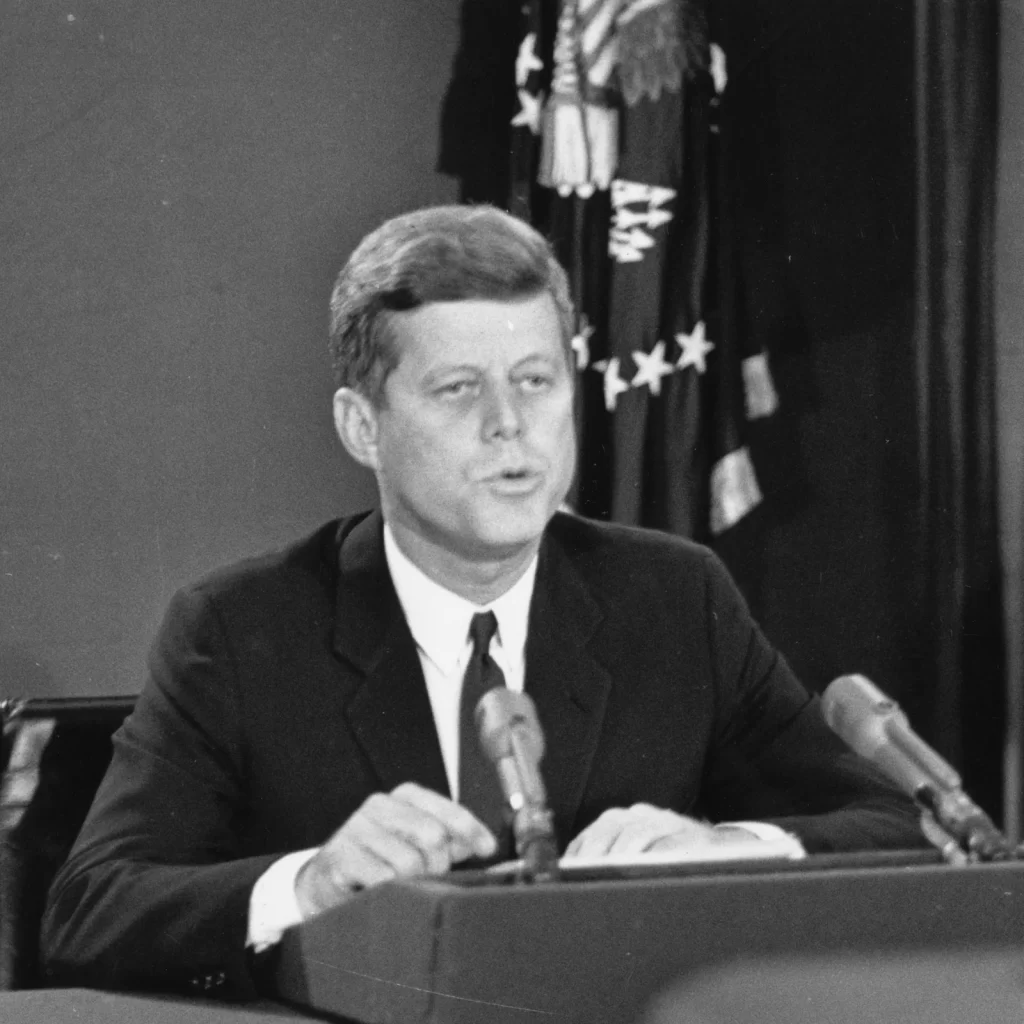

The address to the nation was postponed until Monday night, October 22, 1962. President Kennedy wanted to get it right. There was no rushing into the warning he was about to give the American people. Prior to addressing the American people, President Kennedy called former President Eisenhower. You could hear the trepidation in Kennedy’s voice as he asked the former President if he thought Khrushchev would actually fire a nuclear weapon. President Eisenhower’s response is surprising to President Kennedy. From Listening In:

- JFK – “General, what about if the Soviet Union-Khrushchev-announces tomorrow, which I think he will, that if we attack Cuba that it’s going to be a nuclear war? And what’s your judgment as to the chances they’ll fire these things off if we invade Cuba?”

- Eisenhower – “Oh, I don’t believe they will.”

- JFK – “You don’t think they will?”

- Eisenhower – “No.”

- JFK – “In other words, you would take that risk if the situation seemed desirable?”

- Eisenhower – “Well, as a matter of fact, what can you do?”

At 7:00 p.m. Monday night, October 22, 1962, Kennedy went on national television. He first explained the situation in Cuba and the use of a quarantine to stop the delivery of nuclear missiles. He then emphasized that the blockade was the initial step in the standoff. He emphasized further military action maybe needed and outlined what that maybe. The nation went to bed that Monday night filled with fear and uncertainty. However, they knew what was happening. They were made aware of the situation and felt the government was acting in their best interest. Kennedy had the support of a unified country.

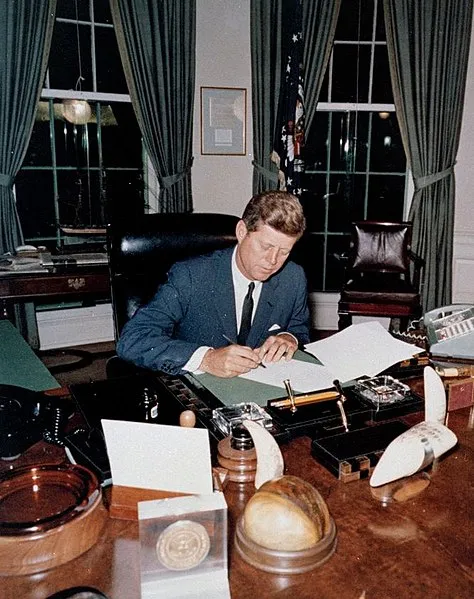

The following day, October 23, 1962, Tuesday, President Kennedy signed Proclamation 3504. The Proclamation authorized the naval quarantine of Cuba. The President was coached to use the word quarantine instead of blockade. The use of the word blockade of anyone’s country could be conceived as an act of war. President Kennedy was playing the English Dictionary and he needed every crafty word he could find.

Adlai Stevenson was President Kennedy’s Ambassador to the United Nations. He was twice the Democratic nominee for President of the United States. Stevenson was seen by both Robert and John Kennedy as a weak politician; a man who lack toughness and was generally puny, per the standards set by a Kennedy. What Kennedy lacked in the world of public opinion was hard proof that the missiles in Cuba were a threat to the United States, the Western Hemisphere, and to the world. If the missiles were activated, the balance of power would change.

At the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the world of public opinion was tried in the United Nations. Thanks to numerous U-2 flights, President Kennedy had his proof. President Kennedy possessed photographs of the missile sites in Cuba. His idea was to provide these photos to Ambassador Stevenson for disclosure at a United Nations meeting and, specifically, setting up the Soviet Ambassador V.A. Zorin in denying the missiles existed. This would then shift the international community in favor of the United States and for ordering the removal of the missiles. However, Robert and other advisors believed Ambassador Stevenson was not strong enough to make such a confrontation against Ambassador Zorin.

After October 23, 1962, the Kennedy’s would never label Stevenson weak or puny. The face-off between Stevenson and Zorin occurred at the United Nations and made history as the most quoted confrontation of the Cuban Missile Crisis. From Thirteen Days, Robert recalls the following exchange:

- Stevenson: “Mr. Zorin, I remind you that the other day you did not deny the existence of these weapons. But today, again, if I heard you correctly, you now say that they do not exist, or that we haven’t proved they exist. All right, sir, let me ask you one simple question. Do you, Ambassador Zorin, deny that the U.S.S.R. has placed and is placing medium and intermediate range missiles and sites in Cuba? Yes or no? Don’t wait for the translation, yes or no?”

- Zorin: “I am not in an American courtroom, sir, and therefore I do not wish to answer a question that is put to me in the fashion in which a prosecutor puts questions. In due course, sir, you will have your answer.”

- Stevenson: “You are in the courtroom of world opinion right now, and you can answer yes or no. You have denied that they exist, and I want to know whether I have understood you correctly.”

- Zorin: “Continue with your statement. You will have your answer in due course.”

- Stevenson: “I am prepared to wait for my answer until hell freezes over, if that’s your decision. And I am also prepared to present the evidence in this room.”

There were almost daily communications between President Kennedy and Premier Khrushchev. But no matter how much they communicated, there was no stopping the blockade or the deployment of U.S. Military personnel. Premier Khrushchev severely underestimated the young President. Once the pictures of the missile sites were revealed and the world saw how far the U.S.S.R. was willing to go in global domination, Khrushchev’s options were limited.

Despite the enormous tension, President Kennedy and Premier Khrushchev found a way out of the volatile situation. Specifically, there were two letters sent by Premier Khrushchev. The first letter, sent October 26, 1962, was casual and contrite. Khrushchev offered to remove the missiles in Cuba in exchange only for the United States not to invade Cuba. On October 27, 1962, President Kennedy received a second letter from Khrushchev. This time, however, the letter was more demanding. President Kennedy and Robert believed Khrushchev did not write the letter. They believed high ranking members of the Russian Communist Party drafted the letter for Khrushchev. In this second letter, Khrushchev told Kennedy the U.S.S.R. would take the missiles out of Cuba only if the American removed missile installations in Turkey.

Officially, President Kennedy decided he would ignore the terms of Khrushchev’s second letter and agree to the terms of the first letter sent to him. However, privately President Kennedy agreed he would abide by the terms of the second letter and remove U.S. missiles in Turkey. President Kennedy believed this was not a strategic disadvantage as the missiles in Turkey should have been removed during the Eisenhower Administration.

President Kennedy and his administration, at the urging of Robert Kennedy, made a determination to accept the terms of the first letter and promised never to invade Cuba. This would be the official position of the United States and they ignored the second letter even existed. Unofficially and privately, President Kennedy promised Khrushchev that he would remove the missiles in Turkey in six months. On October 28, 1962, the crisis drew to a close and the world could breath a little better.

On June 10, 1963, President Kennedy in a Commencement Address at American University stated, “For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.” Yes, the stakes were very high during the Cuban Missile Crisis. However, President Kennedy seemed to understand that it was just not the United States that would suffer should nuclear war occur. It would be the entire planet.

In the same speech, President Kennedy understood that every civilization has made mistakes. It is the bigger person that is not consumed by them and tries to correct them. “Our problems are man made–therefore, they can be solved by man. And man can be as big as he wants. No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings. Man’s reason and spirit have often solved the seemingly unsolvable–and we believe they can do it again.”

Yes, the speech was one of President Kennedy’s fines and the Cuban Missile Crisis was his greatest hour.

Leave a Reply