Introduction

There is nothing that causes a greater annoyance than the issue of bail1 in the criminal justice system (CJS). The prospect of detaining an innocent person until disposition of their case goes against the grain of a democratic society. We are all presumed innocent until proven guilty. With that said, what do we do with the dangerous repeat offender, who is believed to have committed another gruesome crime? Can society be safe in letting him out? What about the rich offender believed to have committed the crime of theft, forgery, or embezzlement? Is the setting of a reasonable monetary bond good enough to ensure his return to court? Let’s not forget the mentally ill or severe drug addicted. Should they even be considered bond eligible in their state of mind?

These issues are haunting society today in the advent of racial and economic justice. There is no dispute black males and the poor are disproportionally detained prior to disposition of their case than their counterparts. However, is pretrial release the arena in which we want to level the playing field? As I will outline below, pretrial release or detention is never an easy decision for a judicial officer to make. First I will start on why the issue of bond must even be addressed. This can be found in the U.S. Constitution.

Pretrial Release and the U.S. Constitution

Prior to the Revolutionary War, it was not uncommon for a person to remain detained pending disposition of their case. Since we were under British rule, the Crown would detain a beggar or a theft with little cause. If you were suspected of committing a crime of violence or immortal behavior, you certainly were not going to be released. These were the Crown’s orders. The local magistrate was to enforce the Crown’s order and he never provided the reason for detention.

During colonial days in America, a person charged with a criminal act was often detained by order of the Crown.

So, after the war was won, the founding fathers determined citizens should never to be held without a warrant issued for proper cause. In doing so, they drafted the 8th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution which states, “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.” That’s all the founding fathers wrote on the subject of bail. They did not define “excessive” nor did the define, “cruel and unusual punishment.”2

The federal government did not address bond after the Revolutionary War. States and local statutes allowed for the setting of monetary bonds and introduced the role of the bondsman. Essentially for much of our nation’s history, after the defendant was arrested, the defendant was brought before a booking sergeant. The booking sergeant would determine the amount of bond according to the statute the defendant was alleged to have violated. The defendant could either sit in jail, pay the entire bond, or pay a bondsman a 10% fee to be released. The bondsman would then pay the bond and ensure the defendant would return to court. During the initial appearance of the defendant, the magistrate would then review the bond and determine if it was “reasonable.” In most cases, because it was set by statute, the bond was reasonable.

At the turn of the 20th Century, particularly in the 1950’s and 1960’s, America began to look at the fairness of the bond system. Was a large segment of society being detained after arrest because of ethnicity, race, or economic backgrounds? Many studies were done and concluded there was indeed an unfairness to the bond system. What was shocking were the studies that revealed a majority of defendant’s would report to court regardless of what conditions were imposed upon them once released. So, why detain a person at all? As a result of these studies, the federal government adopted the most comprehensive bond reform act in 1984.

The Bail Reform Act of 1984

On October 12, 1984, the Bail Reform Act of 1984 was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives clearing the way for it to become the most sweeping piece of crime legislation since the 1960’s. The Bail Reform Act can be found at 18 U.S.C. §§ 3141…3156. The breakdown of the federal statute is as follows:

- § 3141 – Gives judicial officers authority to make determinations regarding bail in all stages of a criminal case.

- § 3142 – Gives U.S. Pretrial Services Officer (USPTSO)3 authority to establish facilities for and conduct the supervision of defendants. It also defines categories of “release and detention” a defendant may be subject to and contains the rules under which the court and parties must proceed relating to matters of bond. There are four categories that a judicial officer can make in respect to custodial status of a defendant pending final disposition:

- release on personal recognizance bond § 3142 (b);

- release on conditions or combinations of conditions as defined by § 3142(c);

- temporarily detained pending further legal matter § 3142(d); or

- detained until disposition of the case § 3142(e).

- §§ 3152…3154 – Pertains to the administration and the supervision authority of pretrial services officers in the federal court system. § 3154 specifically gives pretrial officers the authority to collect information from defendants and other sources relative to bond. Specifically, § 3154(1) gives pretrial services officers the authority to make recommendations as to whether a defendant should be detained or released. If release is recommended, the pretrial services officer is to recommend conditions of release to the court.

The section of the statute that outlines factors for the U.S. Magistrate to make a determination of detention or release is § 3142(g). The factors a magistrate must consider are listed below:

- nature and circumstances of the offense (violent or non-violent);

- weight of the evidence against the defendant;

- history and characteristics of the defendant. This includes prior criminal history, mental health issues, drug abuse, time in the community for which he was arrested, employment, etc. and,

- if the defendant is a danger to themselves or the community.

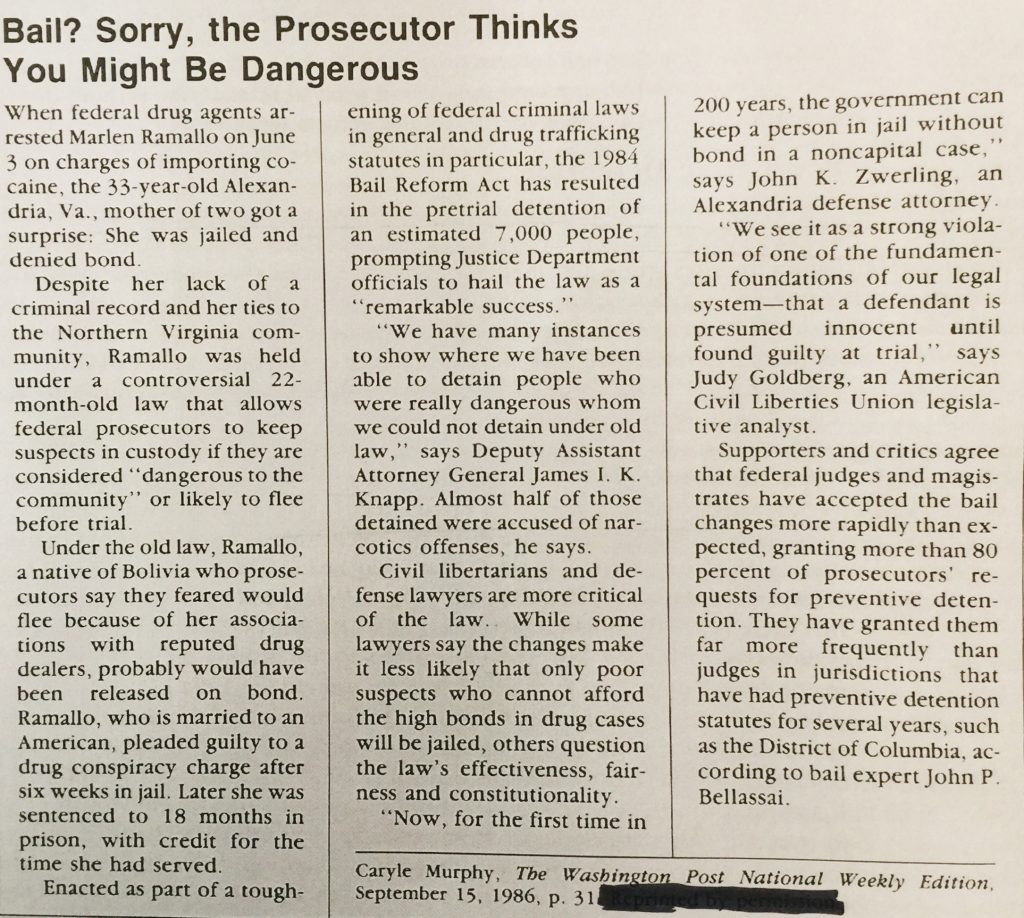

So, that is the Bail Reform Act of 1984 in nutshell. The following article was written by Caryle Murphy on September 15, 1986, and was published in The Washington Post. Although the article is dated, it provides a good insight into the impact this piece of legislation had on the CJS.

The 1984 Bail Reform Act from a Probation Officer’s View

I began my career in probation employment in 1990. I first began working as a state probation officer for the State of Florida. Now you may wonder, what role does a probation officer have with bail? In the state systems a probation officer has very little, if no, role in pretrial release. In the the state of Florida, the probation officer has no role at all. A warrant issued for violation of probation (VOP) was an automatic “no bond.” Essentially, the offender4 stayed in jail until the final VOP hearing. However, on rare occasions during the initial appearance after arrest, the Judge could issue a bond and the probation officer would continue supervising the offender until after the disposition of the VOP.

However, when I went to work for the federal court system, it was an entirely different ball game. The probation officer, working for the court and not an executive agency, played a key role in the determination of bond and bond supervision.

First, immediately after arrest, the probation officer4 interviews the defendant in preparation of a bond report to be submitted to the Judge at the initial appearance. The report contains a recommendation for the Judge, which was based upon two things; risk of flight, and danger to the community. Yes, this is where 18 U.S.C. §§ 3141…3156 comes into play. As a probation officer for the federal court system, it was my duty to scope through this statute and adhere to the strict function of it’s intent. In so doing, I interviewed family members and employer (if any). I also reviewed any arrest, residential, and/or drug abuse and mental health history.

As a probation officer preparing a bond report, you must balance such things as employment, drug use, mental illness, family hardship, to name a few, with the risk of flight or danger to the community. This is not often easy to do. A defendant’s detention or release is ultimately decided by the sitting U.S. Magistrate Judge. However, the court is completely reliant on the information provided by the probation officer.

Second, if the defendant is released on terms and conditions of release, they are supervised by the pretrial officer. Should the defendant violate those terms and conditions, a Petition for Violation of Release Conditions is executed and the defendant is taken back before the Judge to determine if they should continue on bond.

Having worked in both systems. I can honestly say that the federal system, under the Bond Reform Act of 1984, may not be the best system but it does beat the monetary establishment of the bail bondsmen and collateral bond.

In the beginning, I asked if pretrial release was the arena in which we should level the playing field for minorities and/or the poor? After working in the field of probation, it was a very hard decision to recommend release or detention. Ultimately, it is the magistrate that lives with his or her decision. But no matter what the outcome was, I still believe in the creed, “it is better to let 1,000 guilty go free, than have one innocent man detained.”

Notes:

- The use of pretrial release or detention is synonymous with “bond,” “bail,” or “bail status.” The entire period from the point of arrest until final disposition is generally referred to as the defendant’s “bail status.” After arrest, the defendant is either detained or released.

- Later the Supreme Court would incorporate the 8th Amendment into the Due Process Clauses of the 5th and 14th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

- Sometimes these officers are referred to as U.S. Pretrial Services Officers. They have the same power and authority as a U.S. Probation Officer. However, their work is done at the pretrial stage.

- While moving trough the court system until final disposition, the subject is referred to as “defendant.” The term “offender” is used to note someone who has been found guilty of the initial charge.

Leave a Reply