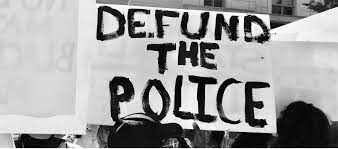

The pendulum of the criminal justice system swings back and forth. It swings between law enforcement and social work. The rate at which the pendulum swings is dependent on the temperament of the country at any given time. Toward the end of the 1960’s, and as a large part in response to the counter culture, America witnessed an unprecedented rise in criminal behavior. As a result of this behavior, cities witnessed an increase in the presence of police and its militarization. In 2020, America saw, by way of video stream, the death of several citizens at the hands of law enforcement. America began to question the tactics and necessity of law enforcement. A new phenomenon hit the media, ‘defund the police.’ However, what does this actually mean? How do you ‘defund’ a necessary governmental entity? First, we must revisit history and witness how law enforcement became so militarized and so well-funded that it consumes the budgets of major metropolitan cities.

A Brief History of Funding Law Enforcement

In 1968, Congress passed the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968. The legislation created the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA) within the Federal Department of Justice. The LEAA’s main purpose was to “assist the States and municipalities in preventing and reducing crime and in improving the performance of the criminal justice system.” In a nutshell, the legislation threw money at local governments in an effort to reduce crime and “increase the effectiveness, fairness, and coordination of law enforcement and criminal justice systems at all levels of government.”[i]

In the 1980’s America witnessed the rise of illegal drug use, in particular crack cocaine. Crack cocaine was something law enforcement had never seen before. Just the way crack cocaine was distributed caught law enforcement and the entire criminal justice community off guard. A crack cocaine dealer could distribute the drug by a hand-to-hand purchase, instead of ‘moving’ large quantities of cocaine.[ii] The payoffs were enormous. However, so were the risks. Along with the big payoffs came the violence surrounded by drug dealers protecting their money, their territory, their livelihood, and their lives. In response to this increase in drug violence, police became more militarized. America saw the birth of the “no knock warrant.” America also saw a rise in drug addiction. President Reagan’s response to this new crime wave was to increase federal funding to local law enforcement and the “just say no” the drug addiction campaign.

In response to the violence and surge in drug use, on October 27, 1986, the U.S. Congress passed Public Law 99-570. It was simply called the “Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986.” The Act created a five (5) year mandatory minimum sentence for possession of five (5) grams or more of crack cocaine, just a few cocaine rocks. By contrast, under the same Act, someone caught with 500 grams or more of powder cocaine, 100 times the amount of cocaine rock, faced a similar five (5) year penalty.[iii] Because crack cocaine was found in urban cities, young black males carried the burden of those penalties. To make us all feel better, a formal declaration of war was declared on drugs.

By the late 1980’s, the U.S. Congress, state legislators, along with state and local police agencies, believed we were losing the war on drugs and decided to militarize law enforcement even more. In order to fight a war, you need equipment, personnel, and training. Not just any equipment, military equipment. Not just any personnel, militarily trained personnel. Of course, not just law

enforcement training, military training.

On November 29, 1989, the U.S. Congress passed the National Defense Authorization Act (NADA) of 1990 and 1991. In this piece of legislation, Congress authorized the transfer of excess Department of Defense equipment to federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies. Specifically, Section 1208 states:

Transfer Authorized – (1) Not withstanding any other provision of law and subject to

subsection (b), the Secretary of Defense may transfer to Federal and State

agencies personal property of the Department of Defense, including small arms

and ammunition, that the Secretary determines is (A) suitable for use by such

agencies in counter-drug activities; and (B) excess to the needs of the

Department of Defense.[iv]

On January 21, 1993, William Jefferson Clinton became the 42nd President of the United States. Along with his agenda, like all U.S. Presidents preceding him, President Clinton took a tough stance on crime. In 1992, Governor Bill Clinton and Senator Al Gore published a book entitled Putting People First, How We Can All Change America. The book highlighted their agenda for America in their upcoming term in office. Regarding crime and drugs, they pledge to, “put more police on the streets and more criminals behind bars.”[v] They pledged to make neighborhoods safe and put, “100,000 new police officers on the streets.”[vi] Once they were in office, they moved on their agenda.

As a result, in 1994, President Clinton and the U.S. Congress passed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act (VCCA) of 1994. According to the Federal Department of Justice (DOJ), as explained in a “Fact Sheet” disseminated on October 24, 1994, the VCCA of 1994, “is the largest crime bill in the history of the country and will provide for 100,000 new police officers, $9.7 billion in funding for prisons and $6.1 billing in funding for prevention programs which were designed with significant input from experienced police officers.”[vii]

The next major piece of crime legislation that came from the U.S. Congress did not specifically address law enforcement but placed emphasis on breaking the cycle of violence and the reentry of inmates into society. The Second Chance Act (SCA) of 2007 was signed into law on April 9, 2008, by President George W. Bush. One major purpose of the SCA of 2007 was to “break the cycle of criminal recidivism, increase public safety, and help States, local units of government, and Indian Tribes, better address the growing population of criminal offenders who return to their communities and commit new crimes.”[viii] The SCA of 2007 does not mention police recruitment and training. It does not guide or advise law enforcement how best to approach the release of repeat offenders in their community. When President Bush signed the SCA of 2007 he stated, “America is the land of second chance, and when the gates of the prison open, the path ahead should be a better way of life.”[ix] The SCA was continued under President Obama. Thus, it became the SCA of 2015, and 2017, respectfully.

Current Defunding Trends In Major Cities

What are some of the immediate trends we are witnessing across America regarding defunding of law enforcement? According to Forbes, at least 13 U.S. cities are cutting funds to their police departments. Below is a summary:

- Austin, Texas $ 150,000,000

- Seattle, Oregon $ 3,500,000

- New York, New York $ 1,000,000,000

- Los Angeles, California $ 150,000,000

- San Francisco, California $ 120,000,000

- Oakland, California $ 1,460,000

- Washington, D.C. $ 15,000,000

- Baltimore, Maryland $ 22,000,000

- Portland, Oregon $ 16,000,000

- Philadelphia, Penn. $ 33,000,000

- Hartford, Connecticut $ 1,000,000

- Norman, Oklahoma $ 865,000

- Salt Lake City, Utah $ 5,300,000

Although New York reduced $1 billion from its police department, it also allocated $354 million toward the homeless, mental illness, and educational services. When Austin, Texas slashed $150 million from its police budget, they cut roughly one third of the current police budget. A city that did not make the above list is the Minneapolis, Minnesota, Police Department (MPD). The MPD has decided to completely dismantle their law enforcement agency.[x]

The Meaning of “Defunding the Police”

Are we to conclude that the above cities are responding to a “knee jerk” reaction? In order to answer this question, we must first determine what does it mean to “defund” a police agency? Dionne Searcey of The New York Times, reported defunding is “spending cuts to police forces that have consumed ever larger shares of city budgets in many cities and towns.”[xi] Searcey’s reporting notes that in some cities the need for law enforcement is shifting to other areas, such as mental health. In Austin, Texas, 911 operators now ask whether a caller is in need of police, fire, or a mental health worker. In Eugene, Oregon, 911 operators deploy teams made up of “a medic and a crisis worker with mental health training to emergency calls.”[xii]

Rashawn Ray of Brookings wrote that defunding the police “means reallocating or redirecting funding away from the police department to other government agencies funded by the local municipality…Defunding does not mean abolish policing.”[xiii]

On June 8, 2020, then presidential candidate, Vice President Joseph Biden weighed in on what he thought “defunding” the police meant. In an interview with CBS Evening News Norah O’Donnell, Ms. O’Donnell asked the Vice President, “do you support defunding the police?” Vice President Biden responded, “No, I don’t support defunding the police. I support conditioning federal aid to police based on whether or not they meet certain basic standards of decency and honorableness.”[xiv] In a sense, Vice President Biden changed the meaning of “defunding” to “conditioning” the police. He would base this “conditioning” on whether or not police agencies were decent and honorable.

Since then, Vice President Biden has moved on to become President Biden. He is the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the United States. As CEO, President Biden is in charge of formulating a budget. The budget is then approved by the U.S. Congress. In formulating this budget, if local law enforcement agencies do not act with decency and respect will their federal funds be cut? This is the same federal aid mentioned earlier passed by the U.S. Congress from the 1960’s to present day.

In order to talk about “defunding” the police, you need to know where the funds are coming from in the first place. Are they coming from a municipal, county, or state budget? Are the funds provided by the federal government in the form of grants and programs? (All governmental budgeting acts in the same manner. The CEO of the local agency enacts a budget and the budget is approved by the local legislative body). We should all agree that cutting funds from a police agency, whether federal, state, or local, inhibits an agency’s ability to provide the service which it was entrusted: to protect and to serve. For, he who controls the budget, controls the agency. Vice President Biden resorted to the word “conditioning” and not “defunding.” His response to take funds away from law enforcement if they do not act honorably and with decency is “defunding” in a parental way. Should local government act in the same manner? In a sense, this is what the Minneapolis, Minnesota, Police Department (MPD) did when it

dismantled the MPD.

Recommendations: Moving Forward

Renaming: “Defunding” the Police

Like any political movement, we often get hooked on a title that does not necessarily reflect the movement itself. For example, in the late 1960’s we had the “Peace Movement.” However, when National Guardsmen killed four (4) students at Ohio State University for demonstrating against the Vietnam War, the movement was hardly peaceful. It was later transformed into the “Anti-War Movement.”

In the late 1990’s and early 2000, there was the “Global Warming” movement brought about by Vice President Al Gore. However, the agenda of the Republican Partywas against any reforms made to protect the planet from “so called” global warming. They cited the needs of the economy came first. When the scientific data was questioned, so was the science itself. Many questioned if the Earth was really “warming.” Was this just a natural cycle? Is the planet really “warming”? Yet the scientific community, news networks, and the Republican Party was fixated on the topic of “Global Warming.” Finally, scientist decided to change this topic of discussion to “Global Climate Change.” A name change that may have brought serious attention to the peril of our dying planet.

So, when we begin a movement to “defund the police,” is that what we are really talking about? Whether it is “defunding,” “dismantling,” or “conditioning,” we can all agree, Republicans and Democrats alike, something needs to be done with excessive use of force by law enforcement, justified or not. Each of these words “defunding,” “dismantling,” or “conditioning,” by itself has such a different meaning. Yet, when used in contemporary times, in the context of law enforcement, they have the exact same meaning. Maybe, we can build on what President Biden said about “conditioning” law enforcement and call it, “The Parenting of Law Enforcement.”

Training

I remember what a Deputy U.S. Marshal told me a long time ago when I first started my career, “not all arrests have to be confrontational and not all confrontations have to end in an arrest.” He was obviously a law enforcement officer with a lot of education and experience. After reviewing the preceding law enforcement Acts, we have to ask, “where is the education and training for law enforcement officers?” The preceding Acts all had one equation: equipment, plus (+) recruitment, divided by (/), the number of arrests, equals (=) a law-abiding community.

In these contemporary times, law enforcement officers must deal with more drug addicts, mental health patients, and homeless, than ever before. How can an officer who has absolutely no training in the field of Substance Use Disorder (SUD) know how to relate to a person addicted to cocaine, opioids, and/or alcohol? How can an officer with zero training in mental health issues know how to even approach a mentally ill person? How about policing a society in which more and more Americans are falling below the poverty level and are finding it difficult to put food on the table? After making an arrest for stealing food to survive, was the officer trained to provide the offender a list of local food banks?

After 2006, when the Second Step Act was passed, a large number of inmates were released from prison. Some of these inmates had been serving lengthy periods of incarceration. Imagine a young law enforcement officer 24 years old, or even younger. The officer comes upon an inmate just released from prison who had been serving a prison sentence of over 26 years, before the officer was even born. This inmate never saw an I-Phone. Before the inmate was incarcerated, you applied for work in person, not online. There was no such thing as a debit card, it was all cash or credit card.

There may not only be a generational gap but also a cultural gap as well. For example, you have a white law enforcement officer, 24 years of age, called to a local convenient store because people loitering outside. The proprietor suspects drugs are being sold and has made similar complaints. The officer sees a black male in his mid to late 40s exit the store. The suspect is just at the door’s threshold but turns back around and goes inside the store. The officer exits the police cruiser. The suspect attempts to leave the store again but is detained because of “suspicious” behavior (running back into the store when the police cruiser pulled into the parking lot). Dispatch informs the officer the suspect was just released from a 26 year sentence of drug trafficking. When asked why he ran back into the store, the following dialogue occurs:

Officer: “Why did you run back into the store when you saw me pull up?”

Suspect: “What? I just ran back in to get my receipt.”

Officer: “Come on now nobody gets a receipt anymore. It is all online, on your bank statement. What do you need a receipt for anyway? Come on let’s see inside the bag. What did you buy?”

Because this is an ongoing investigation for sale of narcotics, and the suspect is a former drug dealer, the officer detains the suspect. He places the suspect in handcuffs and places him in the police cruiser. (This is done so the officer can conduct his investigation. A suspect can be detained while an investigation is ongoing). The contents of the bag revealed an assortment of items the suspect purchased, which the clerk confirmed the suspect paid cash. The officer also asks the clerk if the suspect came back inside to get a receipt and this is also confirmed. The officer goes back to his police cruiser and his suspect. The following dialogue continues:

Officer: “I am going to take you in for further questioning. Your story does not make any sense. Why would you run back into the store to get a receipt you don’t really need? Is it because you were selling drugs just before I pulled up and you needed an alibi?”

Suspect: “Officer, I have been in prison for 26 years. Before I got sent off, you didn’t walk these streets without a receipt with a bag full of items you just purchased. It was a guarantee you were going to get arrested for shoplifting. I don’t know about an online receipt. I don’t even have a bank account. I paid in cash.”

This is a true and verified story as told to this author. The suspect was later released when there was simply no evidence to arrest him for either drug trafficking or shoplifting. Yet, the negative view of law enforcement will still be with this suspect.

We let hundreds of inmates serving generational sentences be released from prison and did nothing to train law enforcement on how to approach these citizens. Many of these citizens have no intention of going back to prison. They are simply burned out. They are paralyzed by how fast technology advanced while they were just doing time. Yet, if they encounter the wrong untrained officer, the situation could be dire. These are areas in which law enforcement need the most basic training.

Donald J. Mihalek is a retired senior Secret Service Regional Training, tactics and firearms instructor. In an article written for The Hill, Professionalize Police Funds And Mandate Training, he noted, “Unfortunately, when a law enforcement agency’s budget is cut, one of the first things to go is training, despite the fact that it is the only way for police departments to professionalize and be responsive to changing community needs.”[xv]In the article, Mihalek quotes the famous Greek philosopher Archilochus, which is very appropriate for our times, “We don’t rise to the level of our expectations, we fall to the level of our training.”[xvi]

Do we make it mandatory for every law enforcement officer to have a college degree? Do we require law enforcement officers to be trained and certified in some kind of mental health and Substance Use Disorder (SUD) awareness?

Funding

The funding of any police department is very political. Most city budgets are spent on protecting its citizens, from first responders to law and order. In reference to city budgeting, one thing is clear, police agencies and first responders are the very DNA of any city budget and must be funded. As Swanson, Territo, and Taylor recognized in 1988, “Successful police executives know that money is the fuel upon which police programs operate. The unwillingness to invest a high level of energy in acquiring and managing financial resources is to pre-establish the conditions for mediocre or worse performance by the police department.”[xvii]

Rather than rely on taxes and the city budget process, there are different strategies a police agency can implement to supplement its budget. They can acquire federal grants. However, through the years federal grants have been drying up and come with many strings attached. Agencies can seek out donation programs and forfeiture laws to add to their inventory. Finally, they can implement some of the least popular methods among the citizenry: user fees; police taxes based upon milage rate; or Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Rewards (a reward given by the IRS for racketeers who do not report their income to the IRS).[xviii]

Training for Mental health and Substance Use Disorder (SUD)

Suppose an animal handler in a zoo handled only elephants and one day the zoo’s director tells him, “we are doing away with the elephants, so, you must now handle the tigers, lions, and leopards.” Would it not be advantageous for the zoo handler to learn about tigers, lions, and leopards? It is no different for a Captain of a large police agency to tell his newly inducted class of recruits “you are going to encounter people who are mentally ill and drug addicts, but you must protect the public from harm.” The new recruits have never been trained on how to approach these citizens. They are the zoo handler being told to handle the tigers, lions, and leopards, with no experience or training.

Peter Scarf, a criminologist at Louisiana State University School of Public Health and Justice painted the picture in a nutshell, “The police become the responders of last resort, and the jails become mental hospitals of last resort.”[xix] Scharf notes police officers in training academies receive between four (4) and twelve (12) hours of mental health training. Yet, these same officers may receive approximately 58 hours of firearms training.[xx]

However, to be able to handle the complexities of mental illness, a simple eight (8) hour course will not do. People obtain higher degrees of education to take care of mentally ill patients. So, are we looking for police officers who wear white coats or blue uniforms? Charlie Ransford, Senior Director of Science and Policy at Cure Violence (a Chicago based nonprofit organization that treats violence with disease control and behavior change methods) opined, “A lot of people are asking – how can we train police to do a better job? But that’s the wrong paradigm…We can’t just put in an eight (8) hour training and expect them to be up to speed with things people get degrees in.”[xxi] Are we at a point requiring all law enforcement officers to have more than just a high school education? Or even a specialized degree that teaches an awareness about mental illness?

Substance Use Disorder (SUD) and addiction are slowly transforming from a criminal behavior to a disease model. However, this author opines, after years of experience supervising SUD offenders, that law enforcement is forced into a vicious cycle with the addict and the dealer. Here is how it goes. The addict is the lowest of the low on a criminal chart in a police chief’s office that could, just could, contain a criminal drug enterprise. A criminal enterprise that threatens his community. So, in order to pierce this criminal enterprise, or make a dent into its nefarious behavior, law enforcement needs the addict. The addict will lead them to who sold them the drug, the price of the drug, and the distribution method. Without the addict’s knowledge, law enforcement has no knowledge of what is transpiring in the drug community or culture.

In his book, Dream Land: The True Tale of Americans Opiate Epidemic, Sam Quinones writes how black tar heroin is distributed in the United States by a group of children from Xalisco, Mexico. Quinones explains how it took years of investigative work by narcotic divisions across the United States to uncover the Xalisco Boys and its network. I highly recommend any individual who feels we must take funds from a police department, in light of the “defunding movement,” to read it.[xxii]

Final Remarks

So where do we go from here? We cannot deny that a movement is underway to curve unnecessary and sometimes deadly use of force by law enforcement. Whatever we call the movement, “defunding,” “dismantling,” or conditioning,” we must understand the cause. Is local law enforcement too militarized? Is local law enforcement not efficiently trained to handle today’s societal and cultural problems?

We cannot be trapped like we were in other movements such as: The Peace Movement, or Global Warming. If we truly “defund” police agencies, what is it that we are doing? We would not provide law enforcement agencies, public safety departments, and/or first responders the funds needed to do their jobs. Instead, we need to increase funding for training and increase education for our most trusted citizens; law enforcement officers.

We got to where we are because of knee jerk responses to what we perceived were threats to our moral fiber. The “War on Crime” got us a more militarized police force with no training on cultural or societal issues. We fought, and lost, a “War on Drugs” because we failed to provide for the necessary training police officers needed to understand the cycle of addiction.

So, for these reasons, this author believes that we should call this much needed movement, “Training the Police on Cultural and Societal Issues.”

Endnotes:

[i] Study By the Staff of the United States General Accounting Office, Overview of Activities Funded By The Law Enforcement Assistance Administration on, November 29, 1977, Document Resume 04309.

[ii] https://www.drugfreeworld.org/drugfacts/crackcocaine/a-short-history.html.

[iii] https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/101hr2461/text

Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986.

[iv] http://govtrackus/congress/bills/101/hr2461/text.

H.R. 2461 (101st): National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal

Years 1990 and 1991.

[v] Bill Clinton and Al Gore, Putting People First, How We Can All Change America (Times Books, a division of Random House, 1992). Pg 71.

[vi] Ibid,

Pg. 72.

[vii]https://www.ncjrsgov//txtfiles//bills.txt, Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, October 24, 1994, NCJ

FS040067.

[viii] 42 U.S.C. 17501(a)(1), U.S. Code – Unannotated.

[ix] https://www.georgewbush-whitehouse.archieves.gov/news/releases/2008/04/print/20080409-15html. The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, Fact Sheet: President Bush Signs Second Chance Act of 2007.

[x] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeminancevoy/2020/08/13/at-least-13-cities-are-defunding-their-police-departments/?sh=1704637b29e3.

[xi] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/08/us/what-does-defund-police-mean.

[xii] Ibid,

endnote XI.

[xiii] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2020/06/19/what-does-defund-the-police-mean-and-does-it-have-merit/.

[xiv] https://www.cbsnews.com/news/biden-federal-aid-epartments-defunding.

[xv] https://www.thehill.com/opinion/criminal-justice/506707-professionalize-police-fund-and-mandate-training.

[xvi] Ibid, endnote XV.

[xvii] Swanson, Charles R.; Territo, Leonard; Taylor, Robert W., (1988). Police Administration: Structures, Processes, and Behavior, 2nd ed., Macmillan Publishing Company, New York. Page 491.

[xviii] Ibid, endnote XVII, pgs. 488 – 491.

[xix] https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/09/18/police-shooting-mental-health-solutions-training-defund/5763145002/.

[xx] Ibid, endnote XIX.

[xxi] Ibid, endnote XIX.

[xxii] Quinones, Sam, Dream Land: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic, Bloomsbury Publishing, New York, 2015.

Leave a Reply